I was recently an invited speaker in a series of STEM talks at Moraine Valley Community College. My talk was called “What can algorithms tell us about life, love, and happiness?” and it’s on Youtube now so you can go watch it. The central theme of the talk was the lens of computation, that algorithms and theoretical computer science can provide new and novel explanations for the natural phenomena we observe in the world.

One of the main stories I told in the talk is about stable marriages and the deferred acceptance algorithm, which we covered previously on this blog. However, one of the examples of the applications I gave was to kidney exchanges and school allocation. I said in the talk that it’s a variant of the stable marriages, but it’s not clear exactly how the two are related. This post will fill that gap and showcase some of the unity in the field of mechanism design.

Mechanism design, which is sometimes called market design, has a grand vision. There is a population of players with individual incentives, and given some central goal the designer wants to come up with a game where the self-interest of the players will lead them to efficiently achieve the designer’s goals. That’s what we’re going to do today with a class of problems called allocation problems.

As usual, all of the code we used in this post is available in a repository on this blog’s Github page.

Allocating houses with dictators

In stable marriages we had $ n$ men and $ n$ women and we wanted to pair them off one to one in a way that there were no mutual incentives to cheat. Let’s modify this scenario so that only one side has preferences and the other does not. The analogy here is that we have $ n$ people and $ n$ houses, but what do we want to guarantee? It doesn’t make sense to say that people will cheat on each other, but it does make sense to ask that there’s no way for people to swap houses and have everyone be at least as happy as before. Let’s formalize this.

Let $ A$ be a set of people (agents) and $ H$ be a set of houses, and $ n = |A| = |H|$. A matching is a one-to-one map from $ A \to H$. Each agent is assumed to have a strict preference over houses, and if we’re given two houses $ h_1, h_2$ and $ a \in A$ prefers $ h_1$ over $ h_2$, we express that by saying $ h_1 >_a h_2$. If we want to include the possibility that $ h_1 = h_2$, we would say $ h_1 \geq_a h_2$. I.e., either they’re the same house, or $ a$ strictly prefers $ h_1$ more.

Definition: A matching $ M: A \to H$ is called pareto-optimal if there is no other matching $ M$ with both of the following properties:

- Every agent is at least as happy in $ N$ as in $ M$, i.e. for every $ a \in A$, $ N(a) \geq_a M(a)$.

- Some agent is strictly happier in $ N$, i.e. there exists an $ a \in A$ with $ N(a) >_a M(a)$.

We say a matching $ N$ “pareto-dominates” another matching $ M$ if these two properties hold. As a side note, if you like abstract algebra you might notice that you can take matchings and form them into a lattice where the comparison is pareto-domination. If you go deep into the theory of lattices, you can use some nice fixed-point theorems to (non-constructively) prove the existences of optimal allocations in this context and for stable marriages. See this paper if you’re interested. Of course, we will give efficient algorithms to achieve our goals, which is how I prefer to live life.

The mechanism we’ll use to find such an optimal matching is extremely simple, and it’s called the serial dictatorship.

First you pick an arbitrary ordering of the agents and all houses are marked “available.” Then the first agent in the ordering picks their top choice, and you remove their choice from the available houses. Continue in this way down the list until you get to the end, and the outcome is guaranteed to be pareto-optimal.

Theorem: Serial dictatorship always produces a pareto-optimal matching.

Proof. Let $ M$ be the output of the algorithm. Suppose the theorem is false, that there is some $ N$ that pareto-dominates $ M$. Let $ a$ be the first agent in the chosen ordering who gets a strictly better house in $ N$ than in $ M$. Whatever house $ a$ gets, call it $ N(a)$, it has to be a house that was unavailable at the time in the algorithm when $ a$ got to pick (otherwise $ a$ would have picked $ N(a)$ during the algorithm!). This means that $ a$ took the house chosen by some agent $ b \in A$ whose turn to pick comes before $ a$. But by assumption, $ a$ was the first agent to get a strictly better house, so $ b$ has to end up with a worse house. This contradicts that every agent is at least as happy in $ N$ than in $ M$, so $ N$ cannot pareto-dominate $ M$.

$$\square$$It’s easy enough to implement this in Python. Each agent will be represented by its list of preferences, each object will be an integer, and the matching will be a dictionary. The only thing we need to do is pick a way to order the agents, and we’ll just pick a random ordering. As usual, all of the code used in this post is available on this blog’s github page.

# serialDictatorship: [[int]], [int] -> {int: int}

# construct a pareto-optimal allocation of objects to agents.

def serialDictatorship(agents, objects, seed=None):

if seed is not None:

random.seed(seed)

agentPreferences = agents[:]

random.shuffle(agentPreferences)

allocation = dict()

availableHouses = set(objects)

for agentIndex, preference in enumerate(agentPreferences):

allocation[agentIndex] = max(availableHouses, key=preference.index)

availableHouses.remove(allocation[agentIndex])

return allocation

And a test

agents = [['d','a','c','b'], # 4th in my chosen seed

['a','d','c','b'], # 3rd

['a','d','b','c'], # 2nd

['d','a','c','b']] # 1st

objects = ['a','b','c','d']

allocation = serialDictatorship(agents, objects, seed=1)

test({0: 'b', 1: 'c', 2: 'd', 3: 'a'}, allocation)

This algorithm is so simple it’s almost hard to believe. But it get’s better, because under some reasonable conditions, it’s the only algorithm that solves this problem.

Theorem [Svensson 98]: Serial dictatorship is the only algorithm that produces a pareto-optimal matching and also has the following three properties:

- Strategy-proof: no agent can improve their outcomes by lying about their preferences at the beginning.

- Neutral: the outcome of the algorithm is unchanged if you permute the items (i.e., does not depend on the index of the item in some list)

- Non-bossy: No agent can change the outcome of the algorithm without also changing the object they receive.

And if we drop any one of these conditions there are other mechanisms that satisfy the rest. This theorem was proved in this paper by Lars-Gunnar Svensson in 1998, and it’s not particularly long or complicated. The proof of the main theorem is about a page. It would be a great exercise in reading mathematics to go through the proof and summarize the main idea (you could even leave a comment with your answer!).

Allocation with existing ownership

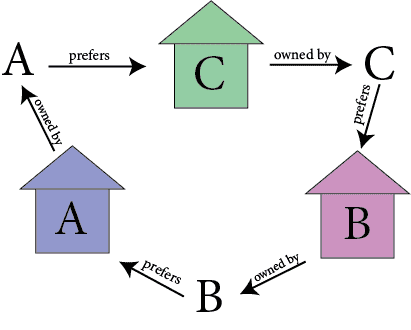

Now we switch to a slightly different problem. There are still $ n$ houses and $ n$ agents, but now every agent already “owns” a house. The question becomes: can they improve their situation by trading houses? It shouldn’t be immediately obvious whether this is possible, because a trade can happen in a “cycle” like the following:

cycles

Here A prefers the house of B, and B prefers the house of C, and C prefers the house of A, so they’d all benefit from doing a three-way cyclic trade. You can easily imagine the generalization to larger cycles.

This model was studied by Shapley and Scarf in 1974 (the same Shapley who did the deferred acceptance algorithm for stable marriages). Just as you’d expect, our goal is to find an optimal (re)-allocation of houses to agents in which there is no cycle the stands to improve. That is, there is no subset of agents that can jointly improve their standing. In formalizing this we call an “optimal” matching a core matching. Again $ A$ is a set of agents, and $ H$ is a set of houses.

Definition: A matching $ M: A \to H$ is called a core matching if there is no subset $ B \subset A$ and no matching $ N: A \to H$ with the following properties:

- For every $ b \in B$, $ N(b)$ is owned by some other agent in $ B$ (trading only happens within $ B$).

- Every agent $ b$ in $ B$ is at least as happy as before, i.e. $ N(b) \geq_b M(b)$ for all $ b$.

- Some agent in $ B$ strictly improves, i.e. for some $ b, N(b) >_b M(b)$.

We also call an algorithm individually rational if it ensures that every agent gets a house that is at least as good as their starting house. It should be clear that an algorithm which produces a core matching is individually rational, because for any agent $ a$ we can set $ B = \{a\}$, i.e. force $ a$ to consider not trading at all, and being a core matching says that’s not better for $ a$. Likewise, core matchings are also pareto-optimal by setting $ B = A$.

It might seem like the idea of a “core” solution to an allocation problem is more general, and you’re right. You can define it for a very general setting of cooperative games and prove the existence of core matchings in that setting. See Wikipedia for more. As is our prerogative, we’ll achieve the same thing by constructing core matchings with an algorithm.

Indeed, the following theorem is due to Shapley & Scarf.

Theorem [Shapley-Scarf 74]: There is a core matching for every choice of preferences. Moreover, one can be found by an efficient algorithm.

Proof. The mechanism we’ll define is called the top trading cycles algorithm. We operate in rounds, and the first round goes as follows.

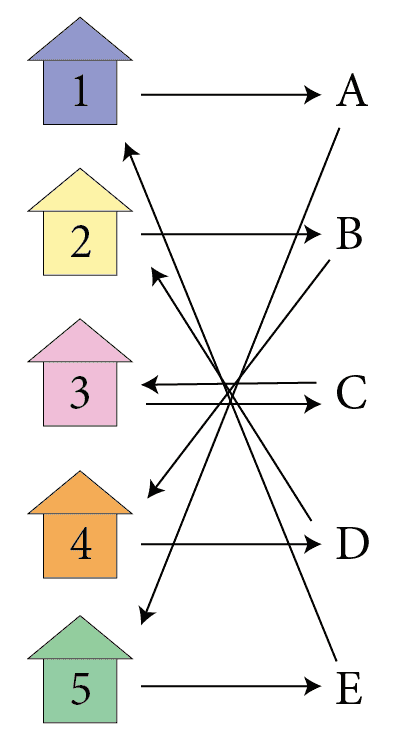

Form a directed graph with nodes in $ A \cup H$. That is there is one node for each agent and one node for each house. Then we start by having each agent “point” to its most preferred house, and each house “points” to its original owner. That is, we add in directed edges from agents to their top pick, and houses to their owners. For example, say there are five agents $ A = \{ a, b, c, d, e, f \}$ and houses $ H = \{ 1,2,3,4,5 \}$ with $ a$ owning $ 1$, and $ b$ owning $ 2$, etc. but their favorite picks goes backwards, so that $ a$ prefers house $ 5$ most, and $ b$ prefers $ 4$ most, $ c$ prefers $ 3$ (which $ c$ also owns), etc. Then the “pointing picture” in the first round looks like this.

ttc-example

The claim about such a graph is that there is always some directed cycle. In the example above, there are three. And moreover, we claim that no two cycles can share an edge. It’s easy to see there has to be a cycle: you can start at any agent and just follow the single outgoing edge until you find yourself repeating some vertices. By the fact that there is only one edge going out of any vertex, it follows that no two cycles could share an edge (or else in the last edge they share, there’d have to be a fork, i.e. two outgoing edges).

In the example above, you can start from A and follow the only edge and you get the cycle A -> 5 -> E -> 1 -> A. Similarly, starting at 4 would give you 4 -> D -> 2 -> B -> 4.

The point is that when you remove a cycle, you can have the agents in that cycle do the trade indicated by the cycle and remove the entire cycle from the graph. The consequence of this is that you have some agents who were pointing to houses that are removed, and so these agents revise their outgoing edge to point at their next most preferred available house. You can then continue removing cycles in this way until all the agents have been assigned a house.

The proof that this is a core matching is analogous to the proof that serial dictatorships were pareto-optimal. If there were some subset $ B$ and some other matching $ N$ under which $ B$ does better, then one of these agents has to be the first to be removed in a cycle during the algorithm’s run. But that agent got the best possible pick of a house, so by involving with $ B$ that agent necessarily gets a worse outcome.

$$\square$$This algorithm is commonly called the Top Trading Cycles algorithm, because it splits the set of agents and houses into a disjoint union of cycles, each of which is the best trade possible for every agent involved.

Implementing the Top Trading Cycles algorithm in code requires us to be able to find cycles in graphs, but that isn’t so hard. I implemented a simple data structure for a graph with helper functions that are specific to our kind of graph (i.e., every vertex has outdegree 1, so the algorithm to find cycles is simpler than something like Tarjan’s algorithm). You can see the data structure on this post’s github repository in the file graph.py. An example of using it:

>>> G = Graph([1,'a',2,'b',3,'c',4,'d',5,'e',6,'f'])

>>> G.addEdges([(1,'a'), ('a',2), (2,'b'), ('b',3), (3,'c'), ('c',1),

(4,'d'), ('d',5), (5,'e'), ('e',4), (6,'f'), ('f',6)])

>>> G['d']

Vertex('d')

>>> G['d'].outgoingEdges

{('d', 5)}

>>> G['d'].anyNext() # return the target of any outgoing edge from 'd'

Vertex(5)

>>> G.delete('e')

>>> G[4].incomingEdges

set()

Next we implement a function to find a cycle, and a function to extract the agents from a cycle. For latter we can assume the cycle is just represented by any agent on the cycle (again, because our graphs always have outdegree exactly 1).

# anyCycle: graph -> vertex

# find any vertex involved in a cycle

def anyCycle(G):

visited = set()

v = G.anyVertex()

while v not in visited:

visited.add(v)

v = v.anyNext()

return v

# getAgents: graph, vertex -> set(vertex)

# get the set of agents on a cycle starting at the given vertex

def getAgents(G, cycle, agents):

# make sure starting vertex is a house

if cycle.vertexId in agents:

cycle = cycle.anyNext()

startingHouse = cycle

currentVertex = startingHouse.anyNext()

theAgents = set()

while currentVertex not in theAgents:

theAgents.add(currentVertex)

currentVertex = currentVertex.anyNext()

currentVertex = currentVertex.anyNext()

return theAgents

Finally, implementing the algorithm is just bookkeeping. After setting up the initial graph, the core of the routine is

def topTradingCycles(agents, houses, agentPreferences, initialOwnership):

# form the initial graph

...

allocation = dict()

while len(G.vertices) &> 0:

cycle = anyCycle(G)

cycleAgents = getAgents(G, cycle, agents)

# assign agents in the cycle their choice of house

for a in cycleAgents:

h = a.anyNext().vertexId

allocation[a.vertexId] = h

G.delete(a)

G.delete(h)

for a in agents:

if a in G.vertices and G[a].outdegree() == 0:

# update preferences

...

G.addEdge(a, preferredHouse(a))

return allocation

This mutates the graph in each round by deleting any cycle that was found, and adding new edges when the top choice of some agent is removed. Finally, to fill in the ellipses we just need to say how we represent the preferences. The input agentPreferences is a dictionary mapping agents to a list of all houses in order of preference. So again we can just represent the “top available pick” by an index and update that index when agents lose their top pick.

# maps agent to an index of the list agentPreferences[agent]

currentPreferenceIndex = dict((a,0) for a in agents)

preferredHouse = lambda a: agentPreferences[a][currentPreferenceIndex[a]]

Then to update we just have to replace the currentPreferenceIndex for each disappointed agent by its next best option.

for a in agents:

if a in G.vertices and G[a].outdegree() == 0:

while preferredHouse(a) not in G.vertices:

currentPreferenceIndex[a] += 1

G.addEdge(a, preferredHouse(a))

And that’s it! We included a small suite of test cases which you can run if you want to play around with it more.

One final nice thing about this algorithm is that it almost generalizes the serial dictatorship algorithm. What you do is rather than have each house point to its original owner, you just have all houses point to the first agent in the pre-specified ordering. Then a cycle will always have length 2, the first agent gets their preferred house, and in the next round the houses now point to the second agent in the ordering, and so on.

Kidney exchange

We still need one more ingredient to see the bridge from allocation problems to kidney exchanges. The setting is like this: say Manuel needs a kidney transplant, and he’s lucky enough that his sister-in-law Anastasia wants to donate her kidney to Manuel. However, it turns out that Anastasia doesn’t the same right blood/antibody type for a donation, and so even though she has a kidney to give, they can’t give it to Manuel. Now one might say “just sell your kidney and use the money to buy a kidney with the right type!” Turns out that’s illegal; at some point we as a society decided that it’s immoral to sell organs. But it is legal to exchange a kidney for a kidney. So if Manuel and Anastasia can find a pair of people both of whom happen to have the right blood types, they can arrange for a swap.

But finding two people both of whom have the right blood types is unlikely, and we can actually do far better! We can turn this into a housing allocation problem as follows. Anyone with a kidney to donate is a “house,” and anyone who needs a kidney is an “agent.” And to start off with, we say that each agent “owns” the kidney of their willing donor. And the preferences of each agent are determined by which kidney donors have the right blood type (with ties split, say, by geographical distance). Then when you do the top trading cycles algorithm you find these chains where Anastasia, instead of donating to Manuel, donates to another person who has the right blood type. On the other end of the cycle, Manuel receives a kidney from someone with the right blood type.

The big twist is that not everyone who needs a kidney knows someone willing to donate. So there are agents who are “new” to the market and don’t already own a house. Moreover, maybe you have someone who is willing to donate a kidney but isn’t asking for anything in return.

Because of this the algorithm changes slightly. You can no longer guarantee the existence of a cycle (though you can still guarantee that no two cycles will share an edge). But as new people are added to the graph, cycles will eventually form and you can make the trades. There are a few extra details if you want to ensure that everyone is being honest (if you’re thinking about it like a market in the economic sense, where people could be lying about their preferences).

The resulting mechanism is called You Request My House I Get Your Turn (YRMHIGYT). In short, the idea is that you pick an order on the agents, say for kidney exchanges it’s the order in which the patients are diagnosed. And you have them add edges to the graph in that order. At each step you look for a cycle, and when one appears you remove it as usual. The twist, and the source of the name, is that when someone who has no house requests a house which is already owned, the agent who owns the house gets to jump forward in the queue. This turns out to make everything “fair” (in that everyone is guaranteed to get a house at least as good as the one they own) and one can prove analogous optimality theorems to the ones we did for serial dictatorship.

This mechanism was implemented by Alvin Roth in the US hospital system, and by some measure it has saved many lives. If you want to hear more about the process and how successful the kidney exchange program is, you can listen to this Freakonomics podcast episode where they interviewed Al Roth and some of the patients who benefited from this new allocation market.

It would be an excellent exercise to go deeper into the guts of the kidney exchange program (see this paper by Alvin Roth et al.), and implement the matching system in code. At the very least, implementing the YRMHIGYT mechanism is only a minor modification of our existing Top Trading Cycles code.

Until next time!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.