Two years ago, Erik Demaine and three other researchers published a fun paper to the arXiv proving that most incarnations of classic nintendo games are NP-hard. This includes almost every Super Mario Brothers, Donkey Kong, and Pokemon title. Back then I wrote a blog post summarizing the technical aspects of their work, and even gave a talk on it to a room full of curious undergraduate math majors.

But while bad tech-writers tend to interpret NP-hard as “really really hard,” the truth is more complicated. It’s really a statement about computational complexity, which has a precise mathematical formulation. Sparing the reader any technical details, here’s what NP-hard implies for practical purposes:

You should abandon hope of designing an algorithm that can solve any instance of your NP-hard problem, but many NP-hard problems have efficient practical “good-enough” solutions.

The very definition of NP-hard means that NP-hard problems need only be hard in the worst case. For illustration, the fact that Pokemon is NP-hard boils down to whether you can navigate a vastly complicated maze of trainers, some of whom are guaranteed to defeat you. It has little to do with the difficulty of the game Pokemon itself, and everything to do with whether you can stretch some subset of the game’s rules to create a really bad worst-case scenario.

So NP-hardness has very little to do with human playability, and it turns out that in practice there are plenty of good algorithms for winning at Super Mario Brothers. They work really well at beating levels designed for humans to play, but we are highly confident that they would fail to win in the worst-case levels we can cook up. Why don’t we know it for a fact? Well that’s the $ P \ne NP$ conjecture.

Since Demaine’s paper (and for a while before it) a lot of popular games have been inspected under the computational complexity lens. Recently, Candy Crush Saga was proven to be NP-hard, but the list doesn’t stop with bad mobile apps. This paper of Viglietta shows that Pac-man, Tron, Doom, Starcraft, and many other famous games all contain NP-hard rule-sets. Games like Tetris are even known to have strong hardness-of-approximation bounds. Many board games have also been studied under this lens, when you generalize them to an $ n \times n$ sized board. Chess and checkers are both what’s called EXP-complete. A simplified version of Go fits into a category called PSPACE-complete, but with the general ruleset it’s believed to be EXP-complete.1 Here’s a list of some more classic games and their complexity status.

So we have this weird contrast: lots of NP-hard (and worse!) games have efficient algorithms that play them very well (checkers is “solved,” for example), but in the worst case we believe there is no efficient algorithm that will play these games perfectly. We could ask, “We can still write algorithms to play these games well, so what’s the point of studying their computational complexity?”

I agree with the implication behind the question: it really is just pointless fun. The mathematics involved is the very kind of nuanced manipulations that hackers enjoy: using the rules of a game to craft bizarre gadgets which, if the player is to surpass them, they must implicitly solve some mathematical problem which is already known to be hard.

But we could also turn the question right back around. Since all of these great games have really hard computational hardness properties, could we use theoretical computer science, and to a broader extent mathematics, to design great games? I claim the answer is yes.

A Case Study: Greedy Spiders

Greedy spiders is a game designed by the game design company Blyts. In it, you’re tasked with protecting a set of helplessly trapped flies from the jaws of a hungry spider.

A screenshot from Greedy Spiders.

In the game the spider always moves in discrete amounts (between the intersections of the strands of spiderweb) toward the closest fly. The main tool you have at your disposal is the ability to destroy a strand of the web, thus prohibiting the spider from using it. The game proceeds in rounds: you cut one strand, the spider picks a move, you cut another, the spider moves, and so on until the flies are no longer reachable or the spider devours a victim.

Aside from being totally fun, this game is obviously mathematical. For the reader who is familiar with graph theory, there’s a nice formalization of this problem.

The Greedy Spiders Problem: You are given a graph $ G_0 = (V, E_0)$ and two sets $ S_0, F \subset V$ denoting the locations of the spiders and flies, respectively. There is a fixed algorithm $ A$ that the spiders use to move. An instance of the game proceeds in rounds, and at the beginning of each round we call the current graph $ G_i = (V, E_i)$ and the current location of the spiders $ S_i$. Each round has two steps:

- You pick an edge $ e \in E_i$ to delete, forming the new graph $ G_{i+1} = (V, E_i)$.

- The spiders jointly compute their next move according to $ A$, and each spider moves to an adjacent vertex. Thus $ S_i$ becomes $ S_{i+1}$.

Your task is to decide whether there is a sequence of edge deletions which keeps $ S_t$ and $ F$ disjoint for all $ t \geq 0$. In other words, we want to find a sequence of edge deletions that disconnects the part of the graph containing the spiders from the part of the graph containing the flies.

This is a slightly generalized version of Greedy Spiders proper, but there are some interesting things to note. Perhaps the most obvious question is about the algorithm $ A$. Depending on your tastes you could make it adversarial, devising the smartest possible move at every step of the way. This is just as hard as asking if there is any algorithm that the spiders can use to win. To make it easier, $ A$ could be an algorithm represented by a small circuit to which the player has access, or, as it truly is in the Greedy Spiders game, it could be the greedy algorithm (and the player can exploit this).

Though I haven’t heard of the Greedy Spiders problem in the literature by any other name, it seems quite likely that it would arise naturally. One can imagine the spiders as enemies traversing a network (a city, or a virus in a computer network), and your job is to hinder their movement toward high-value targets. Perhaps people in the defense industry could use a reasonable approximation algorithm for this problem. I have little doubt that this game is NP-hard,2 but the purpose of this article is not to prove new complexity results. The point is that this natural theoretical problem is a really fun game to play! And the game designer’s job is to do what game designers love to do: add features and design levels that are fun to play.

Indeed the Greedy Spiders folks did just that: their game features some 70-odd levels, many with multiple spiders and additional tools for the player. Some examples of new tools are: the ability to delete a vertex of the graph and the ability to place a ‘decoy-fly’ which is (to the greedy-algorithm-following spiders) indistinguishable from a real fly. They player is usually given only one or two uses of these tools per level, but one can imagine that the puzzles become a lot richer.

Examples

I can point to a number of interesting problems that I can imagine turning into successful games, and I will in a moment, but before I want to make it clear that I don’t propose game developers study theoretical computer science just to turn our problems into games verbatim. No, I imagine that the wealth of problems in computer science can serve as inspiration, as a spring board into a world of interesting gameplay mechanics and puzzles. The bonus for game designers is that adding features usually makes problems harder and more interesting, and you don’t need to know anything about proofs or the details of the reductions to understand the problems themselves (you just need familiarity with the basic objects of consideration, sets, graphs, etc).

For a tangential motivation, I imagine that students would be much more willing to do math problems if they were based on ideas coming from really fun games. Indeed, people have even turned the stunningly boring chore of drawing an accurate graph of a function into a game that kids seem to enjoy. I could further imagine a game that teaches programming by first having a student play a game (based on a hard computational problem) and then write simple programs that seek to do well. Continuing with the spiders example they could play as the defender, and then switch to the role of the spider by writing the algorithm the spiders follow.

But enough rambling! Here is a short list of theoretical computer science problems for which I see game potential. None of them have, to my knowledge, been turned into games, but the common features among them all are the huge potential for creative extensions and interesting level design.

Graph Coloring

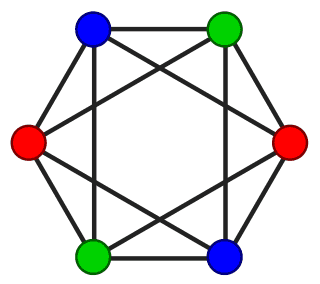

Graph coloring is one of the oldest NP-complete problems known. Given a graph $ G$ and a set of colors $ \{ 1, 2, \dots, k \}$, one seeks to choose colors for the vertices of $ G$ so that no edge connects two vertices of the same color.

coloring

Now coloring a given graph would be a lame game, so let’s spice it up. Instead of one player trying to color a graph, have two players. They’re given a $ k$-colorable graph (say, $ k$ is 3), and they take turns coloring the vertices. The first player’s goal is to arrive at a correct coloring, while the second player tries to force the first player to violate the coloring condition (that no adjacent vertices are the same color). No player is allowed to break the coloring if they have an option. Now change the colors to jewels or vegetables or something, and you have yourself an award-winning game! (Or maybe: Epic Cartographer Battles of History)

An additional modification: give the two players a graph that can’t be colored with $ k$ colors, and the first player to color a monochromatic edge is the loser. Add additional move types (contracting edges or deleting vertices, etc) to taste.

Art Gallery Problem

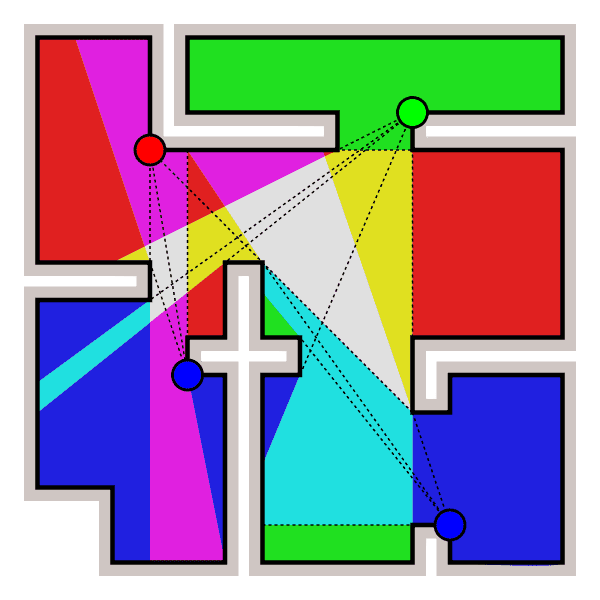

Given a layout of a museum, the art gallery problem is the problem of choosing the minimal number of cameras so as to cover the whole museum.

artgallery

This is a classic problem in computational geometry, and is well-known to be NP-hard. In some variants (like the one pictured above) the cameras are restricted to being placed at corners. Again, this is the kind of game that would be fun with multiple players. Rather than have perfect 360-degree cameras, you could have an angular slice of vision per camera. Then one player chooses where to place the cameras (getting exponentially more points for using fewer cameras), and the opponent must traverse from one part of the museum to the other avoiding the cameras. Make the thief a chubby pig stealing eggs from birds and you have yourself a franchise.

For more spice, allow the thief some special tactics like breaking through walls and the ability to disable a single camera.

This idea has of course been the basis of many single-player stealth games (where the guards/cameras are fixed by the level designer), but I haven’t seen it done as a multiplayer game. This also brings to mind variants like the recent Nothing to Hide, which counterintuitively pits you as both the camera placer and the hero: you have to place cameras in such a way that you’re always in vision as you move about to solve puzzles. Needless to say, this fruit still has plenty of juice for the squeezing.

Pancake Sorting

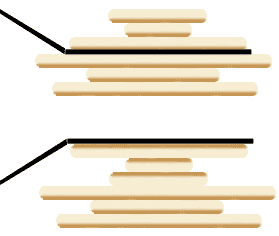

Pancake sorting is the problem of sorting a list of integers into ascending order by using only the operation of a “pancake flip.”

panackesort

Just like it sounds, a pancake flip involves choosing an index in the list and flipping the prefix of the list (or suffix, depending on your orientation) like a spatula flips a stack of pancakes. Now I think sorting integers is boring (and it’s not NP-hard!), but when you forget about numbers and that one special configuration (ascending sorted order), things get more interesting. Instead, have the pancakes be letters and have the goal be to use pancake flips to arrive at a real English word. That is, you don’t know the goal word ahead of time, so it’s the anagram problem plus finding an efficient pancake flip to get there. Have a player’s score be based on the number of flips before a word is found, and make it timed to add extra pressure, and you have yourself a classic!

The level design then becomes finding good word scrambles with multiple reasonable paths one could follow to get valid words. My mother would probably play this game!

Bin Packing

Young Mikio is making sushi for his family! He’s got a table full of ingredients of various sizes, but there is a limit to how much he can fit into each roll. His family members have different tastes, and so his goal is to make everyone as happy as possible with his culinary skills and the options available to him.

Another name for this problem is bin packing. There are a collection of indivisible objects of various sizes and values, and a set of bins to pack them in. Your goal is to find the packing that doesn’t exceed the maximum in any bin and maximizes the total value of the packed goods.

binpacking

I thought of sushi because I recently played a ridiculously cute game about sushi (thanks to my awesome friend Yen over at Baking And Math), but I can imagine other themes that suggest natural modifications of the problem. The objects being packed could be two-dimensional, there could be bonuses for satisfying certain family members (or penalties for not doing so!), or there could be a super knife that is able to divide one object in half.

I could continue this list for quite a while, but perhaps I should keep my best ideas to myself in case any game companies want to hire me as a consultant. 🙂

Do you know of games that are based on any of these ideas? Do you have ideas for features or variations of the game ideas listed above? Do you have other ideas for how to turn computational problems into games? I’d love to hear about it in the comments.

Until next time!

EXP is the class of problems solvable in exponential time (where the exponent is the size of the problem instance, say $ n$ for a game played on an $ n \times n$ board), so we’re saying that a perfect Chess or Checkers solver could be used to solve any problem that can be solved in exponential time. PSPACE is strictly smaller (we think; this is open): it’s the class of all problems solvable if you are allowed as much time as you want, but only a polynomial amount of space to write down your computations. ↑ ↩︎

In the adversarial case it smells like it’s PSPACE-complete, being very close to known PSPACE-hard problems like Cops and Robbers and Generalized Geography. ↩︎

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.