I’m pleased to announce that another paper of mine is finished. This one just got accepted to MFCS 2014, which is being held in Budapest this year (this whole research thing is exciting!). This is joint work with my advisor, Lev Reyzin. As with my first paper, I’d like to explain things here on my blog a bit more informally than a scholarly article allows.

A Recent History of Graph Coloring

One of the first important things you learn when you study graphs is that coloring graphs is hard. Remember that coloring a graph with $ k$ colors means that you assign each vertex a color (a number in $ \left \{ 1, 2, \dots, k \right \}$) so that no vertex is adjacent to a vertex of the same color (no edge is monochromatic). In fact, even deciding whether a graph can be colored with just $ 3$ colors (not to mention finding such a coloring) has no known polynomial time algorithm. It’s what’s called NP-hard, which means that almost everyone believes it’s hopeless to solve efficiently in the worst case.

One might think that there’s some sort of gradient to this problem, that as the graphs get more “complicated” it becomes algorithmically harder to figure out how colorable they are. There are some notions of “simplicity” and “complexity” for graphs, but they hardly fall on a gradient. Just to give the reader an idea, here are some ways to make graph coloring easy:

- Make sure your graph is planar. Then deciding 4-colorability is easy because the answer is always yes.

- Make sure your graph is triangle-free and planar. Then finding a 3-coloring is easy.

- Make sure your graph is perfect (which again requires knowledge about how colorable it is).

- Make sure your graph has tree-width or clique-width bounded by a constant.

- Make sure your graph doesn’t have a certain kind of induced subgraph (such as having no induced paths of length 4 or 5).

Let me emphasize that these results are very difficult and tricky to compare. The properties are inherently discrete (either perfect or imperfect, planar or not planar). The fact that the world has not yet agreed upon a universal measure of complexity for graphs (or at least one that makes graph coloring easy to understand) is not a criticism of the chef but a testament to the challenge and intrigue of the dish.

Coloring general graphs is much bleaker, where the focus has turned to approximations. You can’t “approximate” the answer to whether a graph is colorable, so now the key here is that we are actually trying to find an approximate coloring. In particular, if you’re given some graph $ G$ and you don’t know the minimum number of colors needed to color it (say it’s $ \chi(G)$, this is called the chromatic number), can you easily color it with what turns out to be, say, $ 2 \chi(G)$ colors?

Garey and Johnson (the gods of NP-hardness) proved this problem is again hard. In fact, they proved that you can’t do better than twice the number of colors. This might not seem so bad in practice, but the story gets worse. This lower bound was improved by Zuckerman, building on the work of Håstad, to depend on the size of the graph! That is, unless $ P=NP$, all efficient algorithms will use asymptotically more than $ \chi(G) n^{1 – \varepsilon}$ colors for any $ \varepsilon > 0$ in the worst case, where $ n$ is the number of vertices of $ G$. So the best you can hope for is being off by something like a multiplicative factor of $ n / \log n$. You can actually achieve this (it’s nontrivial and takes a lot of work), but it carries that aura of pity for the hopeful graph colorer.

The next avenue is to assume you know the chromatic number of your graph, and see how well you can do then. For example: if you are given the promise that a graph $ G$ is 3-colorable, can you efficiently find a coloring with 8 colors? The best would be if you could find a coloring with 4 colors, but this is already known to be NP-hard.

The best upper bounds, algorithms to find approximate colorings of 3-colorable graphs, also pitifully depend on the size of the graph. Remember I say pitiful not to insult the researchers! This decades-long line of work was extremely difficult and deserves the highest praise. It’s just frustrating that the best known algorithm to color a 3-colorable graph requires as many as $ n^{0.2}$ colors. At least it bypasses the barrier of $ n^{1 – \varepsilon}$ mentioned above, so we know that knowing the chromatic number actually does help.

The lower bounds are a bit more hopeful; it’s known to be NP-hard to color a $ k$-colorable graph using $ 2^{\sqrt[3]{k}}$ colors if $ k$ is sufficiently large. There are a handful of other linear lower bounds that work for all $ k \geq 3$, but to my knowledge this is the best asymptotic result. The big open problem (which I doubt many people have their eye on considering how hard it seems) is to find an upper bound depending only on $ k$. I wonder offhand whether a ridiculous bound like $ k^{k^k}$ colors would be considered progress, and I bet it would.

Our Idea: Resilience

So without big breakthroughs on the front of approximate graph coloring, we propose a new front for investigation. The idea is that we consider graphs which are not only colorable, but remain colorable under the adversarial operation of adding a few new edges. More formally,

Definition: A graph $ G = (V,E)$ is called $ r$-resiliently $ k$-colorable if two properties hold

- $ G$ is $ k$-colorable.

- For any set $ E’$ of $ r$ edges disjoint from $ E$, the graph $ G’ = (V, E \cup E’)$ is $ k$-colorable.

The simplest nontrivial example of this is 1-resiliently 3-colorable graphs. That is a graph that is 3-colorable and remains 3-colorable no matter which new edge you add. And the question we ask of this example: is there a polynomial time algorithm to 3-color a 1-resiliently 3-colorable graph? We prove in our paper that this is actually NP-hard, but it’s not a trivial thing to see.

The chief benefit of thinking about resiliently colorable graphs is that it provides a clear gradient of complexity from general graphs (zero-resilient) to the empty graph (which is $ (\binom{k+1}{2} – 1)$-resiliently $ k$-colorable). We know that the most complex case is NP-hard, and maximally resilient graphs are trivially colorable. So finding the boundary where resilience makes things easy can shed new light on graph coloring.

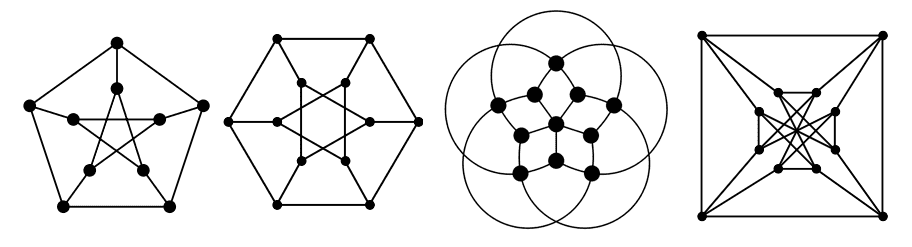

Indeed, we argue in the paper that lots of important graphs have stronger resilience properties than one might expect. For example, here are the resilience properties of some famous graphs.

From left to right: the Petersen graph, 2-resiliently 3-colorable; the Dürer graph, 4-resiliently 4-colorable; the Grötzsch graph, 4-resiliently 4-colorable; and the Chvátal graph, 3-resiliently 4-colorable. These are all maximally resilient (no graph is more resilient than stated) and chromatic (no graph is colorable with fewer colors)

If I were of a mind to do applied graph theory, I would love to know about the resilience properties of graphs that occur in the wild. For example, the reader probably knows the problem of register allocation is a natural graph coloring problem. I would love to know the resilience properties of such graphs, with the dream that they might be resilient enough on average to admit efficient coloring algorithms.

Unfortunately the only way that I know how to compute resilience properties is via brute-force search, and of course this only works for small graphs and small $ k$. If readers are interested I could post such a program (I wrote it in vanilla python), but for now I’ll just post a table I computed on the proportion of small graphs that have various levels of resilience (note this includes graphs that vacuously satisfy the definition).

Percentage of k-colorable graphs on 6 vertices which are n-resilient

k\n 1 2 3 4

----------------------------------------

3 58.0 22.7 5.9 1.7

4 93.3 79.3 58.0 35.3

5 99.4 98.1 94.8 89.0

6 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Percentage of k-colorable graphs on 7 vertices which are n-resilient

k\n 1 2 3 4

----------------------------------------

3 38.1 8.2 1.2 0.3

4 86.7 62.6 35.0 14.9

5 98.7 95.6 88.5 76.2

6 99.9 99.7 99.2 98.3

Percentage of k-colorable graphs on 8 vertices which are n-resilient

k\n 1 2 3 4

----------------------------------------

3 21.3 2.1 0.2 0.0

4 77.6 44.2 17.0 4.5

The idea is this: if this trend continues, that only some small fraction of all 3-colorable graphs are, say, 2-resiliently 3-colorable graphs, then it should be easy to color them. Why? Because resilience imposes structure on the graphs, and that structure can hopefully be realized in a way that allows us to color easily. We don’t know how to characterize that structure yet, but we can give some structural implications for sufficiently resilient graphs.

For example, a 7-resiliently 5-colorable graph can’t have any subgraphs on 6 vertices with $ \binom{6}{2} – 7$ edges, or else we can add enough edges to get a 6-clique which isn’t 5-colorable. This gives an obvious general property about the sizes of subgraphs in resilient graphs, but as a more concrete instance let’s think about 2-resilient 3-colorable graphs $ G$. This property says that no set of 4 vertices may have more than $ 4 = \binom{4}{2} – 2$ edges in $ G$. This rules out 4-cycles and non-isolated triangles, but is it enough to make 3-coloring easy? We can say that $ G$ is a triangle-free graph and a bunch of disjoint triangles, but it’s known 3-colorable non-planar triangle-free graphs can have arbitrarily large chromatic number, and so the coloring problem is hard. Moreover, 2-resilience isn’t enough to make $ G$ planar. It’s not hard to construct a non-planar counterexample, but proving it’s 2-resilient is a tedious task I relegated to my computer.

Speaking of which, the problem of how to determine whether a $ k$-colorable graph is $ r$-resiliently $ k$-colorable is open. Is this problem even in NP? It certainly seems not to be, but if it had a nice characterization or even stronger necessary conditions than above, we might be able to use them to find efficient coloring algorithms.

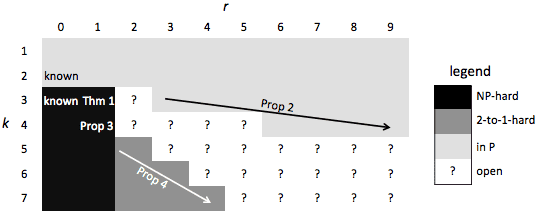

In our paper we begin to fill in a table whose completion would characterize the NP-hardness of coloring resilient graphs

table

Ignoring the technical notion of 2-to-1 hardness, the paper accomplishes this as follows. First, we prove some relationships between cells. In particular, if a cell is NP-hard then so are all the cells to the left and below it. So our Theorem 1, that 3-coloring 1-resiliently 3-colorable graphs is NP-hard, gives us the entire black region, though more trivial arguments give all except the (3,1) cell. Also, if a cell is in P (it’s easy to $ k$-color graphs with that resilience), then so are all cells above and to its right. We prove that $ k$-coloring $ \binom{k}{2}$-resiliently $ k$-colorable graphs is easy. This is trivial: no vertex may have degree greater than $ k-1$, and the greedy algorithm can color such graphs with $ k$ colors. So that gives us the entire light gray region.

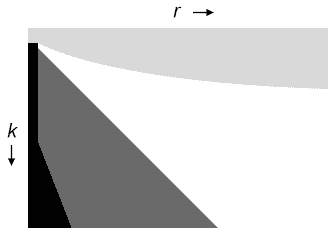

There is one additional lower bound comes from the fact that it’s NP-hard to $ 2^{\sqrt[3]{k}}$-color a $ k$-colorable graph. In particular, we prove that if you have any function $ f(k)$ that makes it NP-hard to $ f(k)$-color a $ k$-colorable graph, then it is NP-hard to $ f(k)$-color an $ (f(k) – k)$-resiliently $ f(k)$-colorable graph. The exponential lower bound hence gives us a nice linear lower bound, and so we have the following “sufficiently zoomed out” picture of the table

zoomed-out

The paper contains the details of how these observations are proved, in addition to the NP-hardness proof for 1-resiliently 3-colorable graphs. This leaves the following open problems:

- Get an unconditional, concrete linear resilience lower bound for hardness.

- Find an algorithm that colors graphs that are less resilient than $ O(k^2)$. Even determining specific cells like (4,5) or (5,9) would likely give enough insight for this.

- Classify the tantalizing (3,2) cell (determine if it’s hard or easy to 3-color a 2-resiliently 3-colorable graph) or even better the (4,2) cell.

- Find a way to relate resilient coloring back to general coloring. For example, if such and such cell is hard, then you can’t approximate k-coloring to within so many colors.

But Wait, There’s More!

Though this paper focuses on graph coloring, our idea of resilience doesn’t stop there (and this is one reason I like it so much!). One can imagine a notion of resilience for almost any combinatorial problem. If you’re trying to satisfy boolean formulas, you can define resilience to mean that you fix the truth value of some variable (we do this in the paper to build up to our main NP-hardness result of 3-coloring 1-resiliently 3-colorable graphs). You can define resilient set cover to allow the removal of some sets. And any other sort of graph-based problem (Traveling salesman, max cut, etc) can be resiliencified by adding or removing edges, whichever makes the problem more constrained.

So this resilience notion is quite general, though it’s hard to define precisely in a general fashion. There is a general framework called Constraint Satisfaction Problems (CSPs), but resilience here seem too general. A CSP is literally just a bunch of objects which can be assigned some set of values, and a set of constraints (k-ary 0-1-valued functions) that need to all be true for the problem to succeed. If we were to define resilience by “adding any constraint” to a given CSP, then there’s nothing to stop us from adding the negation of an existing constraint (or even the tautologically unsatisfiable constraint!). This kind of resilience would be a vacuous definition, and even if we try to rule out these edge cases, I can imagine plenty of weird things that might happen in their stead. That doesn’t mean there isn’t a nice way to generalize resilience to CSPs, but it would probably involve some sort of “constraint class” of acceptable constraints, and I don’t know a reasonable property to impose on the constraint class to make things work.

So there’s lots of room for future work here. It’s exciting to think where it will take me.

Until then!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.