For a list of all the posts on Category Theory, see the Main Content page.

It is time for us to formally define what a category is, to see a wealth of examples. In our next post we’ll see how the definitions laid out here translate to programming constructs. As we’ve said in our soft motivational post on categories, the point of category theory is to organize mathematical structures across various disciplines into a unified language. As such, most of this post will be devote to laying down the definition of a category and the associated notation. We will be as clear as possible to avoid a notational barrier for newcomers, so if anything is unclear we will clarify it in the comments.

Definition of a Category

Let’s recall some examples of categories we’ve seen on this blog that serve to motivate the abstract definition of a category. We expect the reader to be comfortable with sets, and to absorb or glaze over the other examples as comfort dictates. The reader who is uncomfortable with sets and functions on sets should stop here. Instead, visit our primers on proof techniques, which doubles as a primer on set theory (or our terser primer on set theory from a two years ago).

The go-to example of a category is that of sets: sets together with functions between sets form a category. We will state exactly what this means momentarily, but first some examples of categories of “sets with structure” and “structure-preserving maps.”

Groups together with group homomorphisms form a category, as do rings and fields with their respective kinds of homomorphisms. Topological spaces together with continuous functions form a category, and metric spaces with distance-nonincreasing maps (“short” functions) form a sub-category. Vector spaces and linear maps, smooth manifolds and smooth maps, and algebraic varieties with rational maps all form categories. We could continue but the essential idea is clear: a category is some way to specify a collection of objects and “structure-preserving” mappings between those objects. There are three main features common to all of these examples:

- Composition of structure-preserving maps produces structure-preserving maps.

- Composition is associative.

- There is an identity map for each object.

The main abstraction is that forgetting what the objects and mappings are and only considering how they behave allows one to deviate from the examples above in useful ways. For instance, once we see the formal definition below, it will become clear that mathematical (say, first-order logical) statements, together with proofs of implication, form a category. Even though a “proof” isn’t strictly a structure-preserving map, it still fits with the roughly stated axioms above. One can compose proofs by laying the implications out one after another, this composition is trivially associative, and there is an identity proof. Thus, proofs provide a way to “transform” true statements into true statements, preserving the structure of boolean-valued truth.

Another example is the category of ML types and computable functions in ML. Computable functions can be quite wild in their behavior, but they are nevertheless composable, associative, and equipped with an identity.

And so the definition of a category seems to come as a natural consequence to think of all of these examples as special cases of one concept.

Before we state the definition we should note that, for abstruse technical reasons, we cannot phrase the definition of a category as a “set” of objects and mappings between objects. This is already impossible for the category of sets, because there is no “set of all sets.” Somehow (as illustrated by Russell’s paradox) there are “too many” sets to do this. Likewise, there is no “set” of all groups, topological spaces, vector spaces, etc.

This apparent difficulty requires some sidestepping. One possibility is to define a universe of non-paradoxical sets, and define categories by way of a universe. Another is to define a class, which bypasses set theory in another way. We won’t deliberate on the differences between these methods of avoiding Russell’s paradox. The reader need only know that it can be done. For our official definition, we will use the terminology of classes.

Definition: A category $ \textbf{C}$ consists of the following data:

- A class of objects, denoted $ \textup{Obj}(\mathbf{C})$.

- For each pair of objects $ A,B$, a set $ \textup{Hom}(A,B)$ of morphisms. Sometimes these are called hom-sets.

The morphisms satisfy the following conditions:

- For all objects $ A,B,C$ and morphisms $ f \in \textup{Hom}(A,B), g \in \textup{Hom}(B,C)$ there is a composition operation $ \circ$ and $ g \circ f \in \textup{Hom}(A,C)$ is a morphism. We will henceforth drop the $ \circ$ and write $ gf$.

- Composition is associative.

- For all objects $ A$, there is an identity morphism $ 1_A \in \textup{Hom}(A,A)$. For all $ A,B$, and $ f \in \textup{Hom}(A,B)$, we have $ f 1_A = f$ and $ 1_B f = f$.

Some additional notation and terminology: we denote a morphism $ f \in \textup{Hom}(A,B)$ in three ways. Aside from “as an element of a set,” the most general way is as a diagram,

$$\displaystyle A \xrightarrow{\hspace{.5cm} f \hspace{.5cm}} B$$Although we will often shorten a single morphism to the standard function notation $ f: A \to B$. Given a morphism $ f: A \to B$, we call $ A$ the source of $ f$, and $ B$ the target of $ f$.

We will often name our categories, and we will do so in bold. So the category of sets with set-functions is denoted $ \mathbf{Set}$. When working with multiple categories, we will give subscripts on the hom-sets to avoid ambiguity, as in $ \textup{Hom}_{\mathbf{Set}}(A,B)$. A morphism from an object to itself is called an endomorphism, and the set of all endomorphisms of an object $ A$ is denoted $ \textup{End}_{\mathbf{C}}(A)$.

Note that in the definition above we require that morphisms form a set. This is important because hom-sets will have additional algebraic structure (e.g., for certain categories $ \textup{End}_{\mathbf{C}}(A)$ will form a ring).

Examples of Categories

Lets now formally define some of our simple examples of categories. Defining a category amounts to specifying the objects and morphisms, and verifying the conditions in the definition hold.

Sets

Define the category $ \mathbf{Set}$ whose objects are all sets, and whose morphisms are functions on sets. By now it should hopefully be clear that sets form a category, but let us go through the motions explicitly. Every set $ A$ has an identity function $ 1_A(x) = x$, and as we already know, functions on sets compose associatively. To verify this in complete detail would amount to writing down a general function as a relation, and using the definitions from elementary set theory. We have more pressing matters, but a reader who has not seen this before should consult our set theory primer. One can also define the category of finite sets $ \mathbf{FinSet}$ whose objects are finite sets and whose morphisms are again set-functions. As every object and morphism of $ \mathbf{FinSet}$ is one of $ \mathbf{Set}$, we call the former a subcategory of the latter.

Finite categories

The most trivial possible categories are those with only finitely many objects. For instance, define the category $ \mathbf{1}$ to have a single object $ \ast$ and a single morphism $ 1_{\ast}$, which must of course be the identity. The composition $ 1_{\ast} 1_{\ast}$ is forced to be $ 1_{\ast}$, and so this is a (rather useless) category. One can also imagine a category $ \mathbf{2}$ which has one non-identity morphism $ A \to B$ as well as examples of categories with any number of finite objects. Nothing interesting is going on here; we just completely specify the structure of the category object by object and morphism by morphism. Sometimes they come in handy, though.

Poset Categories

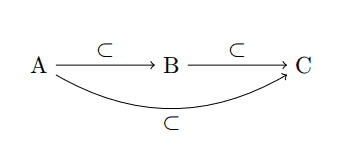

Here is an elementary example of a category that is nonetheless fundamental to modern discussions in topology and algebraic geometry. It will show up again in our work with persistent homology. Let $ X$ be any set, and define the category $ \mathbf{X}_\subset$ as follows. The objects of $ \mathbf{X}_\subset$ are all the subsets of $ X$. If $ A \subset B$ are subsets of $ X$, then the set $ \textup{Hom}(A,B)$ is defined to be the (unique, unnamed) singleton $ A \to B$. Otherwise, $ \textup{Hom}(A,B)$ is the empty set. Identities exist since every set is a subset of itself. The property of being a subset is transitive, so composition of morphisms makes sense and associativity is trivial since there is at most one morphism between any two objects. If the reader doesn’t believe this, we state what composition is rigorously: define each morphism as a pair $ (A,B)$ and define the composition operation as a set-function $ \textup{Hom}(A,B) \times \textup{Hom}(B,C) \to \textup{Hom}(A,C)$, which sends $ ((A,B), (B,C)) \mapsto (A,C)$. Because this operation is so trivial, it seems more appropriate to state it with a diagram:

first-diagram

We say this diagram commutes if all ways to compose morphisms (travel along arrows) have equal results. That is, in the diagram above, we assert that the morphism $ A \to B$ composed with the morphism $ B \to C$ is exactly the one morphism $ A \to C$. Usually one must prove that a diagram commutes, but in this case we are defining the composition operation so that commutativity holds. The reader can now directly verify that composition is associative:

$$(a,b)((b,c)(c,d)) = (a,b)(b,d) = (a,d) = (a,c)(c,d) = ((a,b)(b,c))(c,d)$$More generally, it is not hard to see how any transitive reflexive relation on a set (including partial orders) can be used to form a category: objects are elements of the set, and morphisms are unique arrows which exist when the objects are (asymmetrically) related. The subset category above is a special case where the set in question is the power set of $ X$, and the relation is $ \subset$. The familiar reader should note that the most prominent example of this in higher mathematics is to have $ X$ be the topology of a topological space (the set of open subsets).

Groups

Next, define the category $ \mathbf{Grp}$ whose objects are groups and whose morphisms are group homomorphisms. Recall briefly that a group is a set $ G$ endowed with a sensible (associative) binary operation denoted by multiplication, which has an identity and with respect to which every element has an inverse. For the uninitiated reader, just replace any abstract “group” by the set of all nonzero rational numbers with usual multiplication. It will suffice for this example.

A group homomorphism is a set-function $ f: A \to B$ which satisfies $ f(xy) = f(x)f(y)$ (here the binary operations on the left and right side of the equal sign are the operations in the two respective groups). Being set-functions, group homomorphisms are composable as functions and associatively so. Given any homomorphism $ g: B \to C$, we need to show that the composite is again a homomorphism:

$$\displaystyle gf(xy) = g(f(xy)) = g(f(x)f(y)) = g(f(x))g(f(y)) = gf(x) gf(y)$$Note that there are three multiplication operations floating around in this equation. Groups (as all sets) have identity maps, and the identity map is a perfectly good group homomorphism. This verifies that $ \mathbf{Grp}$ is indeed a category. While we could have stated all of these equalities via commutative diagrams, the pictures are quite large and messy so we will avoid them until later.

A similar derivation will prove that rings form a category, as do vector spaces, topological spaces, and fields. We are unlikely to use these categories in great detail in this series, so we refrain from giving them names for now.

One special example of a category of groups is the category $ \mathbf{Ab}$ of abelian groups (for which the multiplication operation is commutative). This category shows up as the prototypical example of a so-called “abelian category,” which means it has enough structure to do homology.

Graphs

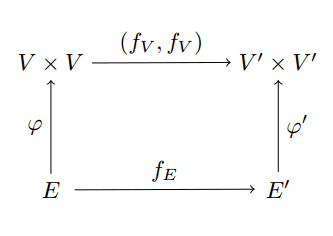

In a more discrete domain, define by $ \mathbf{Graph}$ as follows. The objects in this category are triples $ (V,E, \varphi)$ where $ \varphi: E \to V \times V$ represents edge adjacency. We will usually supress $ \varphi$ by saying vertices $ v,w$ are adjacent instead of $ \varphi(e) = (v,w)$. The morphisms in this category are graph homomorphisms. That is, if $ G = (V,E,\varphi)$ and $ G’ = (V’, E’,\varphi’)$, then $ f \in \textup{Hom}_{\mathbf{Graph}}(G,G’)$ is a pair of set functions on $ f_V: V \to V’, f_E: E \to E’$, satisfying the following commutative diagram. Here we denote by $ (f,f)$ the map which sends $ (u,v) \to (f(u), f(v))$.

graph-hom-diagram

This diagram is quite a mouthful, but in words it requires that whenever $ v,w$ are adjacent in $ G$, then $ f(v), f(w)$ are adjacent in $ G’$. Rewriting the diagram as an equation more explicitly, we are saying that if $ e \in E$ is an edge with $ \varphi(e) = (v,w)$, then it must be the case that $ (f_V(v), f_V(w)) = \varphi'(f_E(e))$. This is how one “preserves” the structure of a graph.

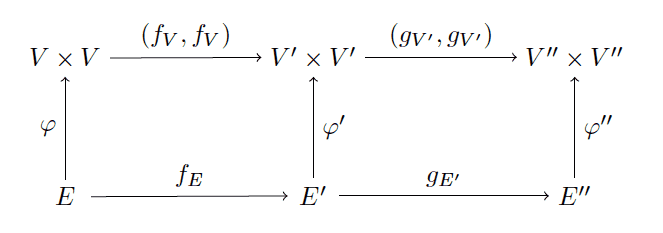

To prove this is a category, we can observe that composition makes sense: given two pairs

$ \displaystyle f_V:V \to V’$

$$\displaystyle f_E: E \to E’$$and

$ \displaystyle g_{V’}: V’ \to V”$

$$\displaystyle g_{E’}: E’ \to E”$$we can compose each morphism individually, getting $ gf_V: V \to V”$ and $ gf_E: E \to E”$, and the following hefty-looking commutative diagram.

graph-commutative

Let’s verify commutativity together: we already know the two squares on the left and right commute (by hypothesis, they are morphisms in this category). So we have two things left to check, that the three ways to get from $ E$ to $ V” \times V”$ are all the same. This amounts to verifying the two equalities

$$\displaystyle (g_{V’}, g_{V’}) (f_V, f_V) \varphi = (g_{V’}, g_{V’}) \varphi’ f_E = \varphi” g_{E’} f_E$$But indeed, going left to right in the above equation, each transition from one expression to another only swaps two morphisms within one of the commutative squares. In other words, the first equality is already enforced by the commutativity of the left-hand square, and the second by the right. We are literally only substituting what we already know to be equal!

If it feels like we didn’t actually do any work there (aside from unravelling exactly what the diagrams mean), then you’re already starting to see the benefits of category theory. It can often feel like a cycle: commutative diagrams make it easy to argue about other commutative diagrams, and one can easily get lost in the wilderness of arrows. But more often than not, devoting a relatively small amount of time up front to show one diagram commutes will make a wealth of facts and theorems follow with no extra work. This is part of the reason category theory is affectionately referred to as “abstract nonsense.”

Diagram Categories**

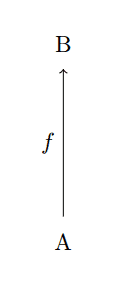

Speaking of abstract nonsense: next up is a very abstract example, but thinking about it will reinforce the ideas we’ve put forth in this post while giving a sneak peek to our treatment of universal properties. Fix an object $ A$ in an arbitrary category $ \mathbf{C}$. Define the category $ \mathbf{C}_A$ whose objects are morphisms with source $ A$. That is, an object of $ \mathbf{C}_A$ looks like

vert-arrow

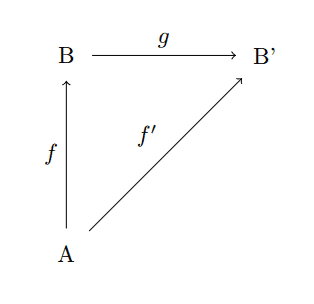

Where $ B$ ranges over all objects of $ \mathbf{C}$. The morphisms of $ \mathbf{C}_A$ are commutative diagrams of the form

diagram-morphism

where as we said earlier the stipulation asserted by the diagram is that $ f’ = gf$. Let’s verify that the axioms for a category hold. Suppose we have two such commutative diagrams with matching target and source, say,

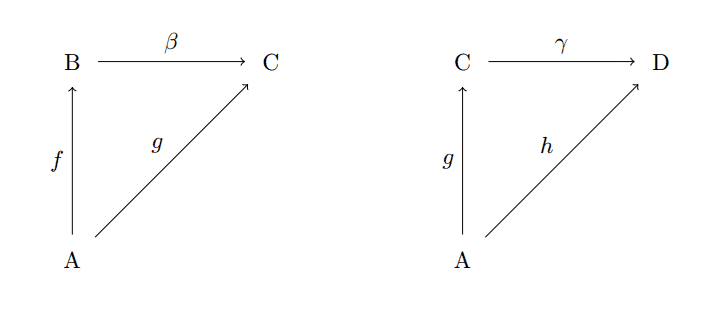

composing-diagram-morphisms

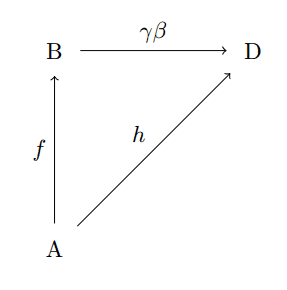

Note that the arrows $ g: A \to C$ must match up in both diagrams, or else composition does not make sense! Then we can combine them into a single commutative diagram:

composed-diagram-morphism

If it is not obvious that this diagram commutes, we need only write down the argument explicitly: by the first diagram $ \beta f = g$ and $ \gamma g = h$, and piecing these together we have $ \gamma \beta f = \gamma g = h$. Associativity of this “piecing together” follows from the associativity of the morphisms in $ \mathbf{C}$. The identity morphism is a diagram whose two “legs” are both $ f: A \to B$ and whose connecting morphism is just $ 1_B$.

This kind of “diagram” category is immensely important, and we will revisit it and many variants of it in the future. A quick sneak peek: this category is closely related to the universal properties of polynomial rings, free objects, and limits.

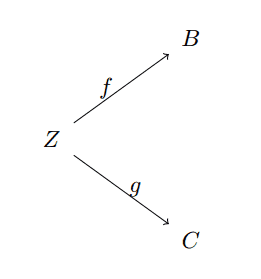

As a slight generalization, you can define a category whose objects consist of pairs of morphisms with a shared source (or target), i.e.,

pairs-category

We challenge the reader to write down what a morphism of this category would look like, and prove the axioms for a category hold (it’s not hard, but a bit messy). We will revisit categories like this one in our post on universal properties; this particular one is intimately related to products.

Next Time

Next time we’ll jump straight into some code, and realize the definition of a category as a type in ML. We’ll see how some of our examples of categories here can be implemented using the code, and inspect the pro’s and con’s of the computational version of our definition.

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.