I recently posted an exploratory piece on why programmers who are genuinely interested in improving their mathematical skills can quickly lose stamina or be deterred. My argument was essentially that they don’t focus enough on mastering the basic methods of proof before attempting to read research papers that assume such knowledge. Also, there are a number of confusing (but in the end helpful) idiosyncrasies in mathematical culture that are often unexplained. Together these can cause enough confusion to stymie even the most dedicated reader. I have certainly experienced it enough to call the feeling familiar.

Now I’m certainly not trying to assert that all programmers need to learn mathematics to improve their craft, nor that learning mathematics will be helpful to any given programmer. All I claim is that someone who wants to understand why theorems are true, or how to tweak mathematical work to suit their own needs, cannot succeed without a thorough understanding of how these results are developed in the first place. Function definitions and variable declarations may form the scaffolding of a C program while the heart of the program may only be contained in a few critical lines of code. In the same way, the heart of a proof is usually quite small and the rest is scaffolding. One surely cannot understand or tweak a program without understanding the scaffolding, and the same goes for mathematical proofs.

And so we begin this series focusing on methods of proof, and we begin in this post with the simplest such methods. I call them the “basic four,” and they are:

- Proof by direct implication

- Proof by contradiction

- Proof by contrapositive, and

- Proof by induction.

This post will focus on the first one, while introducing some basic notation we will use in the future posts. Mastering these proof techniques does take some practice, and it helps to have some basic mathematical content with which to practice on. We will choose the content of set theory because it’s the easiest field in terms of definitions, and its syntax is the most widely used in all but the most pure areas of mathematics. Part of the point of this primer is to spend time demystifying notation as well, so we will cover the material at a leisurely (for an experienced mathematician: aggravatingly slow) pace.

Recalling the Basic Definitions of Sets

Before one can begin to prove theorems about a mathematical object, one must have a thorough understanding of what the object is. In higher mathematics these objects can become prohibitively complicated and abstract, but for our purposes they are quite familiar.

A set is just a collection of things. Obviously there is a more mathematically rigorous formalization of what a set is, but for the purposes of learning to do proofs this is unnecessarily verbose and not constructive. For finite sets in particular and many kinds of infinite sets, absolutely nothing problematic can happen. Somehow, paradoxes only occur in really large sets. We will never need such monstrosities in our theoretical investigations or their applications. So in this post we’ll just work with finite sets and infinite sets of integers so as to better focus on the syntactical scaffolding of a proof.

There are many ways to define sets. One of the easiest is simply to list its elements:

$$\displaystyle X = \left \{ 1,4,9,16,25 \right \}$$The bracket notation simply means the stuff inside is a set. This particular set contains some square numbers. The order here is irrelevant, and sets are not allowed to have repetition. The programmer may think of this as a hash set, a Python set, or simply a list in which duplication is forbidden. The time it takes to apply operations to sets is of no concern for us, so any perspective is valid and multiple perspectives are encouraged for a deeper understanding. There are other ways to describe sets which were the inspiration for list comprehensions in many programming languages. For instance, one way to use the notation is

$$\displaystyle X = \left \{ n^2 : n = 1, \dots, 5 \right \}$$Speaking out loud as I write this, I would say, “Let X be the set of n-squared as n goes from 1 to 5.” This would be a slightly more compact way of writing the set above containing the first five squares. The colon there simply separates the expression to be evaluated at each step from the iteration part. The corresponding list comprehension in Python would be

[n*n for n in range(1,6)]

Cousin to the names from programming, this mathematical notation is called “set-builder notation.” Interestingly enough, mathematicians tend not to use strict set-builder notation. Except when the most stringent of formalities if required, they use words over these iterative expressions. This is part of how flexible mathematics allows us to define things. We might not even know an iterative method for computing numbers, so we could say something like:

$$\displaystyle \left \{ n : n \textup{ is prime } \right \}$$or

$$\displaystyle X = \left \{ n : n \textup{ is a square and } n \leq 1000 \right \}$$There is one bit of non-rigorousness already here! Can you spot it?

The trick is that we don’t have a definition of what it means to be a square. In particular, the observant reader would note that all positive numbers are “squares” if we allow for real numbers, and if we allow for complex numbers we get the negative numbers, too! This is a groan-inducing “gotcha,” but it expresses how important context is in mathematical proof. Depending on the context, this set could be finite or infinite. Now let’s say you encounter such a statement in a real work of mathematics, and there is no obvious clarification? You consider the two possible alternatives: either the set they’re defining is all numbers, or they actually mean a specific set of integers which are squares. The active reader must infer that the former is pointless (why describe all numbers in this stupid way), so the author must mean the latter. Of course, it is not always so obvious what the author intends to convey, but if all one has available is the printed word, this extra step of analyzing the author’s own constructions is necessary.

And so let’s formalize this just a little more.

$$\displaystyle X = \left \{ n : n \textup{ is the square of a positive integer and } n \leq 1000 \right \}$$If we don’t know how to express a condition, we can always just state it in words. The reader should practice at unpacking set-builder expressions in the same way that one can unpack triply-nested Python list comprehensions, but don’t let it become a hindrance to expressing an idea. It’s just that set-builder notation is often easier to parse than words in proofs which construct sets in nit-picky ways. It’s even common for someone presenting a proof to spend a good two minutes or more describing the contents of a tricky set-builder expression before continuing with a proof (the other day I was describing a technical construction to a colleague and we spent the better half of fifteen minutes interpreting and critiquing it).

One interesting bit of notation dictates membership of something inside a set. This is the “set membership” operator, denoted by the $ \in$ symbol (it comes from an odd way of writing a lower-case epsilon; for a short historical deviation, see this stackexchange question I asked on this topic). A programmer would probably feel most comfortable thinking of it as an expression evaluating to true or false, as in the Python code

7 in [1,3,4,5,8,9]

Which evaluates to False. The semantics are identical in mathematics, only the notation doubles as a test and as an assertion of membership. That is, we could translate the above Python expression into mathematical notation:

Let $ X = \left \{ 1,3,4,5,8,9 \right \}$. Then $ 7 \not{\in} X$.

The slash through the $ \in$ represents the test’s negation. We could have also said, “Then it is not the case that $ 7 \in X$.”

Or we could declare that $ X$ must satisfy the property that $ 7 \in X$ (assuming nothing else we know about $ X$ would stop that from happening):

Let $ X$ be any set such that $ 7 \in X$.

Here we are defining this object $ X$ to be as general as possible while still having 7 as a member (perhaps we want to prove something special about all sets which contain 7, although I can’t imagine what that might be).

The last definition we want to make before we start doing proofs is that of the notation for some common sets. The set of natural numbers is

$ \mathbb{N} = \left \{ 1, 2, 3, \dots \right \}$,

and the set of integers is likewise

$ \mathbb{Z} = \left \{ \dots, -2,-1,0,1,2, \dots \right \}$.

The blackboard-bold N stands for “natural” and the blackboard-bold Z stands for “Zahlen,” the German word for “numbers.” (Zero is not a natural number, and if you don’t like it you can go become a logician.)

Subsets, and Direct Implication

The first thing mathematicians want to do when they encounter a new mathematical object is to come up with useful ways to relate them to each other. One such way is by one set “containing” another. Of course, the sense that we mean “contain” requires specification. For on one hand, we could be saying that $ X$, a set, contains as a member another set $ Y$ (nothing stops sets from being elements of other sets). But this is not what we mean. Instead, we want to say that $ X$ contains every element that $ Y$ does. This calls for a new definition:

Definition: A set $ Y$ is a subset of a set $ X$ if every element of $ Y$ is also an element of $ X$. We denote the fact that $ Y$ is a subset of $ X$ with the “subset symbol” $ Y \subset X$.

We often say, “$ Y$ contains $ X$” to mean $ X \subset Y$, or alternatively that, “$ X$ is contained in $ Y$.”

Just as a quick example, the set $ \left \{ 5,8,12 \right \} \subset \left \{ 1, \dots, 20 \right \}$ because the latter contains 5, 8, and 12 as well as all of its other contents.

This new relationship gives us a bit to play with. For the question now becomes: how can we prove that one set is a subset of another set? Of course if they are finite then we can just check every single element by hand, but as programmers we know better than to waste our time with manual verification. The technique becomes more obvious when we start to play with some examples.

Let me define two sets with set-builder notation as follows:

$$\displaystyle X = \left \{ n^2 : n \in \mathbb{N} \right \}$$ $$\displaystyle Y = \left \{ n^4 : n \in \mathbb{N} \right \}$$Take a moment to be sure you understand what the members of these sets are before continuing.

The salient question is, “Is $ Y \subset X$? And if so how can we prove it?” This is where direct implication comes in. What we’re asking is whether it’s true that no matter which element you pick from $ Y$, it will be a member of $ X$. In the most formal language, we are trying to prove the implication that for any number $ y$, if $ y \in Y$ then $ y \in X$.

This is a logical statement of the form $ p \to q$ (read “p implies q”). We will see three ways to prove a statement like this in our methods of proof series, but the most direct way to do it is called direct implication. In particular, we assume that $ p$ is true, and using only logical steps, reach the fact that $ q$ is true. That is, we go directly from “p” to “q.” This method of proof is so common that there is usually no mention of it in a proof before one applies it! It is, in a sense, the “obvious” way to go about proving something.

And so let’s prove the subset question above has an affirmative answer. To do this, we can start by fixing an arbitrary element $ y \in Y$. By “arbitrary” we just mean that whatever follows in the proof will be true if you replace $ y$ by any concrete element of $ Y$. Since there are infinitely many of them, this is really the only way we can proceed.

Now comes the tricky part. This is quite a simple problem, and the reader has probably already figured out the solution, but in general there is no way to proceed from here without creativity. Once one has figured out the scaffolding, one needs to make the “leap” from something which is obviously the “p” to something which is obviously the “q.” This can take the form of playing with the problem until an idea sparks, or it can result in applying a number of previously proved facts.

For this problem, we can achieve the leap by expanding the definitions of what it means to be in each of these sets, and apply a lick of algebra. We know that $ y \in Y$ is a fourth-power of a number. That is, it is $ y = n^4$ for some natural number $ n$. By our knowledge of algebra,

$$n^4 = n \cdot n \cdot n \cdot n = (n \cdot n)^2$$And so $ y$ is indeed the square of a number (it is the square of $ n^2$), and hence $ y \in X$. This concludes the proof that $ Y \subset X$.

Let’s do one more direct implication proof about subsets, and have it be a tad more abstract. That is, we won’t know anything concrete about the members of the sets we’re working with.

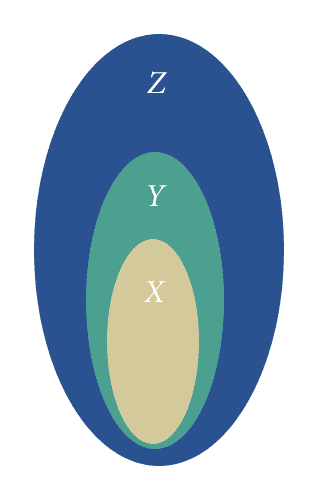

Proposition: Let $ X, Y, Z$ be arbitrary sets. If $ X \subset Y$ and $ Y \subset Z$, then $ X \subset Z$.

Before we continue, rewrite the thing we’re trying to prove as a $ p \to q$ type statement. Then we’ll start by assuming the “p” is true and try to conclude the “q.” In fact, this statement can be really expanded into one of the form

$$((a \to b) \textup{ and } (b \to c)) \to (a \to c)$$In doing this we’re making a serious notational mess of a truly simple statement, bordering on an act of violence. On the other hand, it helps to be able to write things out in complete detail when one doesn’t understand one part of it. The active reader will determine exactly what the propositions $ a, b, c$ represent in the above implication, and this will make the following proof routine to follow.

Another important point to make is that if the proposition is still unclear at this point (or it is unclear how to proceed), then the best line of attack is to write down lots and lots of examples. This is the kind of thing that almost always goes unsaid in any mathematical proof, because one simply assumes that if the reader does not understand what is being asked then they will work with examples until they understand.

For instance, we can come up with a very simple example with finite sets:

$$X = \left \{ 1, 5, 9 \right \}$$ $$Y = \left \{ 1, 2, 5, 7, 9 \right \}$$ $$Z = \left \{ 1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9 \right \}$$In this special case the statement of the theorem is obvious: the conditions hold as expected, and the result holds as well: $ X \subset Z$. We can also do it with some infinite sets:

$$X = \left \{ 4,8,12,16, \dots \right \}$$ $$Y = \left \{ 2, 4, 6, 8, 10, \dots \right \}$$ $$Z = \left \{ 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, \dots \right \}$$Indeed, there is a very simple picture proof hiding under the surface here! It is just:

transitivity-of-subsets

From this picture it should be obvious: if $ X$ is contained in $ Y$ and $ Y$ contained in $ Z$ then $ X$ is obviously contained in $ Z$. With all of this intuitive knowledge under our belt, we can proceed to the formal proof of the statement.

Proof. Suppose that $ x$ is an arbitrary element of $ X$. We want to prove that $ x \in Z$. Applying the first fact that $ X \subset Y$, we know that every element of $ X$ is an element of $ Y$, so $ x \in Y$. Further, by the fact that $ Y \subset Z$, it follows that $ x \in Z$, as desired. $ \square$

This was a bit more formal and a bit more condensed than our last proof, but the syntactical structure was the same. We wanted to prove a $ p \to q$ fact, and we started by assuming the “p” part and deriving the “q” part. All in a day’s work!

Here are some more examples of statements that you can prove by direct implication:

- Let $ A, B, C$ be sets. Show that if $ A \subset B$ and $ B \subset C$ and $ C \subset A$, then $ A = B = C$ (where by equality of sets we mean they have precisely the same elements; as a side note, can you define equality in terms of set containment?).

- The union of two sets $ A, B$ is the set $ A \cup B$ defined by $ \left \{ x : x \in A \textup{ or } x \in B \right \}$. Prove $ A \subset A \cup *$*

- The intersection of two sets $ A, B$ is the set $ A \cap B$ defined by $ \left \{ x : x \in A \textup{ and } x \in B \right \}$. Prove $ A \cap B \subset A$.

- Let $ A,B,C$ be sets, and suppose that $ A \subset B$. Prove that $ A \cap C \subset B \cap C$ and $ A \cup C \subset B \cup C$.

Here are two more exercises from number theory that might require a bit more inspiration:

- Prove that every odd integer is a difference of two square integers.

- Prove that if $ a,b$ are integers then $ a^2 + b^2 \geq 2ab$.

As usual, the first step should be writing down examples, and then attempting a proof.

Proofs by direct implication are very often straightforward, but as a reader we must be cognizant of when it’s being applied. As is often the case in mathematics, the precise method of proof goes unstated except in pedagogy.

Just to get a taste of where else proof by direct implication can show up, we will prove something about functions (in a programming language).

Definition: Let $ f$ be a function in a programming language. We call $ f$ injective if different inputs to $ f$ produce different outputs (and every input produces some output). For the sake of this post, we assume the method of comparing things for equality is fixed across all objects in the language (say, via Java’s object comparison method equals(), or Python’s overloadable == operator).

Proposition: If $ f, g$ are injective functions which can be composed (all outputs of $ f$ are valid inputs to $ g$), then the composition $ gf$ defined by $ gf(x) = g(f(x))$ is injective.

Proof. Let $ x,y$ be two different inputs to $ f$. They are also inputs to $ gf$. Then the values $ f(x), f(y)$ are different, and they are also inputs to $ g$. So $ g(f(x))$ and $ g(f(y))$ are different, proving $ gf$ is injective. $ \square$

Next Time, and a Reference

Next time we’ll investigate the next simplest way to prove statements of the form $ p \to q$: the proof by contrapositive implication. This will involve a slight digression into the general meaning of $ p \to q$. After that we’ll cover contradiction, and then proofs by induction.

Of course, this series is woefully incomplete by the nature of blogs. For those who are interested in proof techniques for the sake of transitioning to advanced mathematics, I recommend Paul Halmos’s Naive Set Theory. For those interested in getting a better idea of the beautiful nature of proofs (that is, mathematics done for the sake of finding clever and beautiful arguments) and want a more casual read, I recommend Paul Lockhart’s Measurement. Both are valuable and well-written texts.

Until next time!

Want to respond? Send me an email, post a webmention, or find me elsewhere on the internet.